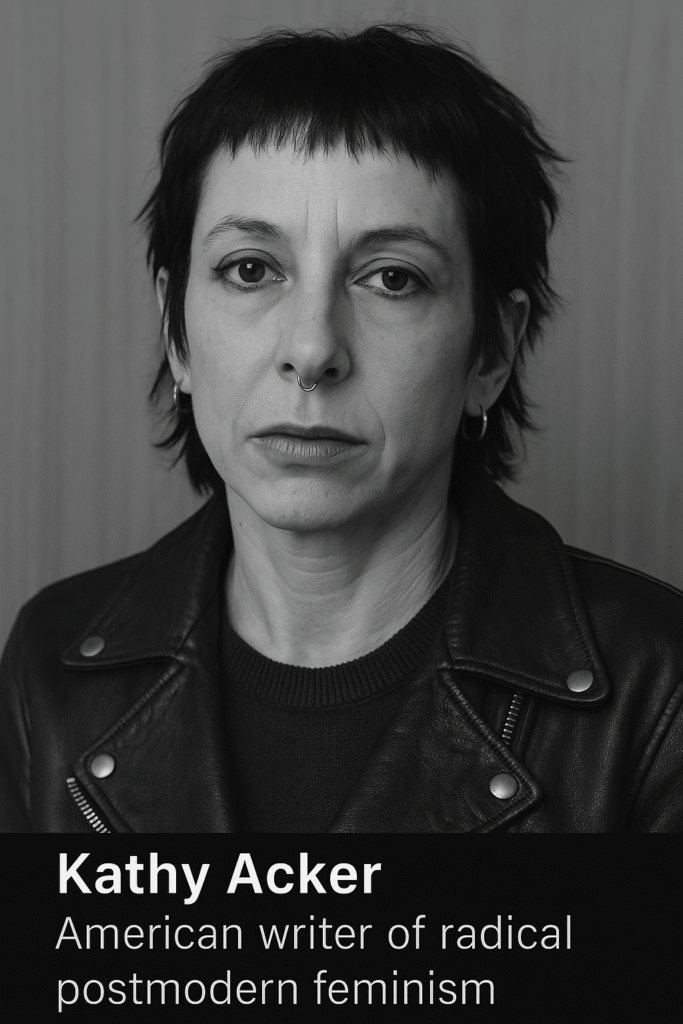

Early Life and New York Roots

Kathy Acker American Writer was born on April 18, 1947, in New York City. Her early years were filled with instability and loneliness. Before she was born, her father left, leaving emotional scars that shaped her defiant nature. Her mother’s suicide in Acker’s twenties deepened her disillusionment and rebellion. However, she found escape in books and words. She read Rimbaud, Burroughs, and Genet, seeking inspiration from their chaos. Moreover, she studied philosophy and classics, blending intellect with underground grit. The city’s noise and art became her education. She learned survival through performance and passion, not order. Later, she graduated from Brandeis University, but her true lessons came from nightlife, libraries, and punk venues. She rejected conformity and embraced resistance. From the beginning, she chose rebellion as identity. Consequently, every sentence she wrote later reflected that raw defiance, merging personal trauma with artistic transformation.

First Writings and Experimental Journals

Kathy Acker American writer entered the literary world through underground zines and small presses. During the 1970s, she published her first pieces in mimeographed magazines filled with radical ideas. She combined autobiography, myth, and raw emotion with pornography and politics. Additionally, she used fragmentation, collage, and repetition to challenge traditional storytelling. Her writing became both rebellion and ritual. She borrowed fearlessly from other authors, openly reshaping their works into her chaotic reflections. She inserted herself into fiction, claiming ownership over every stolen line. Furthermore, she viewed language as combat, using words like weapons. Her writings provoked, shocked, and confused readers and critics alike. She didn’t seek approval or structure. Instead, she sought exposure of hidden truths. Her early masterpiece, The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, introduced her fragmented voice, nonlinear rhythm, and emotional rawness. It embodied her artistic manifesto.

Blood and Guts in High School

In 1978, Acker published Blood and Guts in High School, her most shocking and daring work. The novel exploded boundaries by mixing collage, poetry, dreams, and illustrations. Moreover, it followed Janey Smith, a young girl trapped in cycles of abuse and desire. Janey’s experiences exposed patriarchal cruelty and female suffering. The story’s form shifted constantly, forcing readers into discomfort. It used obscene confessions and fragmented narration to mirror trauma’s distortion. Additionally, the novel refused closure or comfort. It was both confession and protest. The combination of diary, map, and drawing blurred genres entirely. Critics called it obscene, brilliant, or insane. However, the chaos was deliberate. Through Janey, Acker portrayed survival as defiance. Her language became rebellion. The novel remains controversial yet iconic, establishing her as one of the most fearless experimental voices in twentieth-century literature.

Rewriting as Revolution

Kathy Acker American writer redefined literary rebellion through deliberate plagiarism and rewriting. She stole canonical works not to imitate but to destroy authority. She rewrote Great Expectations, Don Quixote, and The Scarlet Letter to inject her voice and female anger. Moreover, she turned male-centered stories into feminist confrontations. Her method exposed the hypocrisy of originality. She argued that all stories are theft, all language shared. Through this belief, she exposed patriarchal authorship as illusion. She didn’t hide her theft; she flaunted it proudly. Furthermore, she turned every rewritten scene into war against literary control. Her language wounded norms and healed individuality. Her art questioned ownership, authorship, and morality itself. She refused boundaries between crime and creativity. Consequently, rewriting became revolution, and her voice became the battlefield’s cry for linguistic freedom.

Don Quixote: A Feminist Rebirth

In 1986, Acker published Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream, one of her most subversive novels. It wasn’t translation or homage—it was confrontation. She reimagined the legendary knight as a modern woman seeking abortion, freedom, and identity. Her heroine’s journey unfolded through hallucinations, diary fragments, and violence. Moreover, Acker mocked religion, romantic ideals, and patriarchal morality. She mixed dreams and philosophy until reality fractured completely. The novel exposed how women fight through madness, pain, and self-invention. Additionally, Acker used absurdity to show liberation’s cost. The text rejected reason, preferring chaos as honesty. Her Don Quixote destroyed meaning to rediscover truth. Thus, she transformed literary history into feminist revolution. The result became a defining feminist postmodern work—one where despair and imagination merged into radical rebirth.

Themes: Identity, Language, Body, Power

Kathy Acker American writer centered her art on unstable identity and power’s violence. Her narrators changed names, genders, and perspectives constantly. Moreover, she explored how language controls bodies and how pain becomes knowledge. She questioned who owns desire and who profits from oppression. Her works portrayed sex as both resistance and prison. She revealed capitalism’s control over intimacy, showing how the body becomes marketplace. Additionally, she confronted cultural hypocrisy through shocking imagery. Her fiction examined loneliness, betrayal, disease, and memory as survival forms. She blended pornography with philosophy to expose contradictions. Her writing refused cure or comfort. It gave voice to suffering with raw honesty. Ultimately, her themes intertwined art, trauma, and power, creating literature that bleeds but never hides.

Performance and Punk Culture

Acker didn’t limit her rebellion to writing; she lived performance as literature. She read onstage dressed in leather, shouting over punk bands with fearless energy. Moreover, she performed her texts like musical scores—loud, messy, and defiant. She treated every word as spell or scream. In London during the 1980s, she joined punk circles, working alongside musicians and artists. Her performances merged theater, music, and rebellion. Additionally, she recorded spoken-word albums that blended eroticism, anger, and intellect. Her stage presence turned poetry into spectacle, her voice into protest. She made her body part of her art, breaking walls between life and text. Through performance, she transformed literature into living resistance, proving that writing breathes when it confronts the crowd directly.

My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Published in 1984, My Death My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini blended autobiography and resurrection. Acker wrote as both herself and Pasolini, merging identities across death and art. Moreover, she questioned what it means to die creatively. She intertwined martyrdom and survival, turning death into aesthetic ritual. Through philosophical fragments, letters, and hallucinations, she blurred boundaries between writer and ghost. Additionally, she explored politics of violence and art’s complicity in it. The text revealed her obsession with transformation through destruction. Her voice shifted between genders, bodies, and faiths. The novel challenged traditional autobiography, presenting identity as a shared echo. In combining personal despair with cultural critique, Acker created her own mythology. She declared that death, like art, exists only through language’s memory.

Language, Form, and Subversion

Kathy Acker American writer shattered the foundations of storytelling itself. She abandoned plot, order, and linear logic. Instead, she followed rhythm, emotion, and chaos. Her writing placed pornography beside philosophy, journal entries beside political essays. Moreover, she replaced chapters with dreams and arguments. Her syntax twisted violently, reflecting fragmented consciousness. She made grammar bleed into rhythm. Her pages forced readers to confront discomfort. Additionally, she disrupted time, allowing moments to overlap and contradict. Her novels didn’t resolve; they broke continuously. Through this chaos, she freed form from structure. She proved that narrative clarity often hides repression. Her subversion exposed language as control and creation as rebellion. In the end, she turned words into living protest, ensuring her art forever resists taming.

Feminism and Radical Sexuality

Kathy Acker American writer transformed feminist writing through radical sexual honesty. She used sexuality not as pleasure but as rebellion. Her characters explored desire as war against control. Moreover, she revealed how female bodies face social and linguistic imprisonment. Her explicit scenes attacked moral hypocrisy, not morality itself. She stripped away shame and replaced it with power. Additionally, she merged sexuality with philosophy, turning eroticism into critique. She forced readers to confront violence, guilt, and pleasure together. Her feminism rejected softness and demanded confrontation. She didn’t preach equality; she exposed power’s cruelty. Her writing questioned purity, love, and gender roles continuously. Through desire, she rebuilt identity on her own terms. Ultimately, she created feminism that screamed, bled, and lived beyond rules. Her eroticism became intellectual, spiritual, and revolutionary—a weapon against silence and obedience.

Politics and Power Structures

Acker viewed writing as revolution against political systems disguised as order. She believed language mirrors state control. Moreover, she showed how capitalism manipulates desire and imagination. Her novels attacked power structures directly, exposing corruption behind authority. She portrayed bureaucracy as emotional and spiritual imprisonment. Additionally, she used violent humor to undermine seriousness. Her fiction revealed political structures as cages built from words. She believed rebellion begins in the mind and continues through language. Therefore, she used literature as resistance training. Every phrase challenged obedience. Moreover, she denied comfort, forcing readers to face complicity. Her political rage burned through metaphors, diaries, and dreamscapes. She dismantled government, gender, and morality together. Through relentless questioning, she exposed how domination hides inside everyday speech. Ultimately, Acker replaced politics of control with politics of chaos, where freedom begins through disobedience.

Love, Betrayal, and Survival

Kathy Acker American writer turned love into battlefield and confession alike. Her relationships inspired emotional and artistic turmoil. She portrayed love as addiction, control, and rebellion. Moreover, she explored betrayal as self-discovery. She viewed heartbreak as creative awakening, not tragedy. Her lovers often mirrored social oppression, revealing patterns of submission. Additionally, she treated affection as experiment, constantly redefining connection and loss. Through letters and monologues, she explored loneliness as resistance to conformity. She sought authenticity within emotional collapse. Furthermore, she believed love exposes identity’s fragility. Her characters desired fiercely yet feared belonging. Each relationship became mirror of survival. In breaking hearts, she found creation. Through emotional brutality, she uncovered truth. Ultimately, she proved that tenderness and violence coexist naturally in human experience, and that love, when destroyed, transforms into the courage necessary for artistic and personal rebirth.

Body as Battlefield

For Acker, the human body represented both prison and revolution. She viewed flesh as language written by power. Moreover, she turned pain into expression. Through tattoos, illness, and eroticism, she explored identity’s physical reality. Her body-centered imagery rejected abstract intellect. Additionally, she believed truth begins inside blood and bone. She treated body as battlefield where culture fights for control. Every scar carried history and defiance. Moreover, she depicted disease and sex as rebellion’s language. Her work during her cancer years intensified this philosophy. She refused to separate suffering from meaning. The body’s vulnerability became sacred. Through flesh, she explored life’s urgency. Ultimately, Acker turned physicality into philosophy. She transformed pain into poetry and mortality into empowerment, declaring that language lives within the skin and rebellion begins through acknowledging every wound as creative, conscious resistance.

Aesthetics of Violence

Violence shaped Acker’s entire artistic vision and emotional vocabulary. She used brutality to expose power’s ugliness. Moreover, her violent scenes shocked readers into awareness. She viewed violence as both destruction and revelation. Her writing didn’t glorify pain—it analyzed control. Additionally, she showed how institutions normalize cruelty through language. Her characters suffered yet transformed that suffering into consciousness. She broke narrative bones to show how control deforms thought. Moreover, her violent imagery turned literature into war zone. She wanted readers to feel discomfort, not safety. Her words ripped apart hypocrisy and sentimentality. Through creative violence, she demanded awakening. Ultimately, she proved art must disturb to liberate. She used aesthetic shock to pierce numbness, forcing moral reflection. Therefore, every scream in her fiction became act of resistance, and every wound opened door toward truth and freedom.

Relation with Other Writers

Kathy Acker American writer built strong intellectual kinship with radical artists and thinkers. She admired William Burroughs for his fragmented form and brutal honesty. Moreover, she borrowed from his cut-up technique while adding feminist intensity. She also shared philosophical rebellion with Jean Genet, embracing transgression as sacred art. Additionally, she found kinship with experimental writers like Gertrude Stein and Marguerite Duras. Her friendships extended into punk circles and performance art spaces. She collaborated, argued, and inspired through letters and readings. Furthermore, she challenged literary elitism by blurring boundaries between art and life. She didn’t compete with male authors—she devoured their language to rebuild it. Ultimately, her relationship with writers was one of collision and transformation. Every borrowed phrase became rebirth, every conversation rebellion, and every influence weaponized against conformity’s suffocating grip.

Reputation and Controversy

Controversy followed Acker throughout her career, fueling both criticism and fascination. Her work offended censors and confused critics. Moreover, her open plagiarism and explicit content provoked endless debate. Some labeled her obscenity as artistic failure. Others hailed her bravery as revolutionary. Additionally, she thrived on scandal, treating outrage as validation. She refused compromise, challenging literary institutions directly. Her readings often drew both admiration and hostility. Furthermore, feminist circles debated her approach to sexuality and violence. She courted contradiction deliberately, using shock as mirror. For her, scandal meant relevance. Every argument proved art still mattered. Ultimately, her controversial reputation preserved her power. She understood that rebellion demands risk. Through provocation, she forced literature to confront truth, showing that art loses strength when it avoids discomfort or refuses confrontation with the boundaries that define morality.

Illness and Defiance

Kathy Acker American writer faced cancer with the same fierce rebellion defining her art. She treated illness as narrative, not tragedy. Moreover, she turned physical decay into philosophical awakening. She refused medical authority and sought healing through alternative methods. Her cancer journey became artistic metaphor for resistance. Additionally, she explored death through writing, confronting fear without surrender. She used diaries and letters to transform despair into awareness. Her defiance deepened, not faded. Furthermore, she redefined survival through language, not medicine. Illness became dialogue between body and consciousness. She believed dying reveals life’s urgency. Through vulnerability, she achieved spiritual clarity. Ultimately, she faced death without submission. Her illness confirmed her lifelong message: rebellion never ends. Even in pain, she refused silence, proving that defiance defines existence more powerfully than comfort or compliance ever could.

Influence on Postmodernism

Acker transformed postmodernism by making it emotional, female, and political. She fused theory with anarchy, showing that thought must live through passion. Moreover, she expanded postmodernism beyond academic games. She filled it with flesh, violence, and confession. Her writing questioned power inside every structure, from grammar to government. Additionally, she replaced irony with urgency. She treated identity as fragmented art form. Her work influenced writers like Chris Kraus, Dodie Bellamy, and Eileen Myles. Furthermore, her approach reshaped feminist postmodern thought entirely. She taught that the personal and political cannot separate. Her novels became manifestos of self-destruction and rebirth. Ultimately, Acker redefined postmodern literature as weapon, mirror, and scream. Her influence endures through every experimental voice daring to mix chaos with clarity and rebellion with revelation.

Death and Legacy

Kathy Acker died in 1997, but her words continue breathing rebellion. Her death marked transformation, not disappearance. Moreover, she became legend of artistic defiance. Her writings remain studied, quoted, and reinterpreted globally. Additionally, her influence extends through feminist, queer, and experimental literature. She inspired generations to write without apology. Her death reflected her belief that creation never ends. Furthermore, she turned mortality into creative metaphor. Every text she left behind defies silence. Her legacy proves literature thrives through confrontation, not comfort. Readers rediscover her courage through every line. Ultimately, she remains symbol of fearless art. Her voice still burns with anger and tenderness. Through defiance, she conquered oblivion, proving that rebellion outlives the body and that words, when written with blood and conviction, defeat both time and erasure.

Language, Form, and Subversion

Language for Acker was weapon, mirror, and playground simultaneously. She believed words imprison thought when used obediently. Therefore, she broke sentences deliberately. She cut, rearranged, and distorted grammar. Moreover, she used repetition as rebellion. Each line became act of deconstruction. Additionally, she rejected beauty without truth. Her writing resembled graffiti on literature’s polished walls. She wanted readers to feel disoriented and alive. Through fragmentation, she exposed manipulation hidden inside communication. She made readers question meaning itself. Furthermore, she turned chaos into method. She demanded emotional honesty within linguistic violence. Ultimately, her subversive form created language that lived, screamed, and demanded confrontation. Acker proved that destruction can birth creativity, and that writing, when fearless, becomes act of freedom rather than ornament—a weapon against silence and obedience disguised as literary tradition.

Dreams and the Unconscious

Acker viewed dreams as doorways into forbidden language. She believed unconscious thought exposes truth more effectively than reason. Therefore, she translated dreams into chaotic poetry. Moreover, she treated surreal imagery as rebellion against logic. She used nightmares as philosophical tools. Additionally, she blended Freud with punk energy. Her dream passages revealed both trauma and transformation. She believed dreams resist censorship naturally. Furthermore, she explored memory’s fragmentation through symbolic violence. She viewed the unconscious as battlefield where identity reshapes itself. Every dream became confession, prophecy, and curse simultaneously. Through dream logic, she dismantled authority’s control over meaning. Her surreal prose exposed the irrational roots of fear and desire. Ultimately, she turned the subconscious into creative revolution, proving imagination remains humanity’s truest rebellion against structures of domination disguised as reason and moral certainty.

Gender and Identity Fluidity

Acker refused fixed identity. She saw gender as performance, not essence. Moreover, she believed labels suffocate individuality. Her characters changed bodies, voices, and desires continually. Additionally, she mixed masculine violence with feminine tenderness. She exposed gender norms as tools of control. Her writing predated queer theory’s popularity. Furthermore, she celebrated androgyny, erotic fluidity, and rebellion against binaries. She argued that language shapes gender more than biology. Therefore, she rewrote womanhood as multiplicity. Every self became performance of transformation. Through unstable identity, she achieved ultimate freedom. Moreover, her fiction showed gender as revolution of being, not limitation. Ultimately, she made identity movement rather than definition. Her characters lived between categories, creating space for liberation. Through constant transformation, she proved identity’s strength comes from flexibility, not conformity, and that chaos sustains authenticity more deeply than stability.

Mythology and Ancient Voices

Kathy Acker American writer revived mythology through rebellion and personal anguish. She rewrote classical heroes as fractured symbols of oppression. Moreover, she replaced gods with broken humans. Her reinterpretations merged myth and autobiography. Additionally, she used ancient texts to challenge modern systems of control. She borrowed Greek tragedy to describe urban despair. Her rewriting of myths dismantled hierarchy and ownership. Furthermore, she gave new voices to forgotten heroines. She used mythology to explore repetition of violence across history. Through symbolic inversion, she created space for female power. Moreover, she treated ancient epics as contemporary manifestos. Her use of myth revealed continuity between past tyranny and modern submission. Ultimately, she turned mythology into living protest, proving that timeless stories still scream against obedience, and that literature reclaims divinity when rebellion replaces reverence.

Literature as Performance

Acker performed literature physically and emotionally. She read aloud with fury, rhythm, and theatricality. Moreover, she treated performance as ritual rebellion. Her readings felt like punk concerts rather than academic events. Additionally, she used stage presence to challenge literary distance. She demanded participation, not observation. Her gestures transformed silence into movement. Furthermore, she connected voice and body through performance art. Her writing came alive through spoken confrontation. She blurred lines between reading, acting, and protest. Moreover, she used public readings to reclaim power over interpretation. She proved meaning changes through presence. Every performance became confession and confrontation together. Ultimately, she transformed literature into communal experience. Through body, rhythm, and emotion, she erased boundary between author and audience, proving that words breathe fully only when performed through passion and unapologetic physicality.

Influence on Feminist Theory

Acker’s feminism reshaped academic and artistic discourse permanently. She expanded feminist theory beyond moral and social reform. Moreover, she introduced rage, chaos, and erotic violence into intellectual debate. She taught that liberation demands confronting ugliness. Additionally, she exposed patriarchy not only in politics but in language. Her writing anticipated later feminist thinkers exploring embodiment and trauma. Furthermore, she replaced politeness with urgency. She turned theory into lived experience. Through creative anarchy, she challenged elitist feminism. Moreover, she refused ideological purity, insisting on contradiction. Her work became weapon for academic rebellion. Ultimately, she redefined feminist theory as living, bleeding organism, alive with contradiction, pain, and transformation—a theory built through survival rather than perfection and through fearless truth rather than respectability or intellectual safety within patriarchal expectations.

Technology and Textual Mutation

Acker foresaw digital culture’s arrival before its vocabulary existed. She imagined cyberspace through textual experimentation. Moreover, she saw machines as metaphors for power and fragmentation. She used textual mutation to explore identity’s artificiality. Additionally, she mixed computer logic with bodily emotion. She compared code to language’s corruption. Furthermore, she believed technology mirrors control and desire. Her fragmented narratives anticipated online disconnection. She wrote about mechanical reproduction long before internet age. Moreover, she viewed digital text as rebellion against ownership. Her style reflected endless cut-and-paste aesthetics. Through textual mutation, she predicted identity crisis caused by virtual reality. Ultimately, she treated technology not as threat but as revelation, showing that digital chaos mirrors psychological breakdown and that truth survives only when form collapses under pressure of information overload.

Reader as Co-Creator

Acker viewed readers as collaborators, not consumers. She rejected traditional storytelling control. Moreover, she invited confusion intentionally. Her fragmented narratives forced readers to build coherence. Additionally, she believed reading requires creative effort. Through discomfort, she ensured engagement. Furthermore, she replaced passive interpretation with active construction. She wrote not for entertainment but awakening. Readers had to confront themselves within her pages. Moreover, she erased boundary between author and audience. She believed understanding demands risk. Therefore, her readers became participants in rebellion. Each interpretation revealed self-confrontation. Her work rewarded those who endured uncertainty. Ultimately, she redefined reading as creation, not reception, proving that literature achieves meaning only through shared struggle between writer, reader, and the dangerous freedom of imagination.

Cultural Resistance and Underground Spirit

Acker lived through New York’s punk underground and carried its defiance into literature. She believed culture begins in rebellion, not institutions. Moreover, she admired chaos as source of authenticity. She worked among outsiders, musicians, and anarchists. Additionally, she treated every poem as protest. Her underground spirit defied commercialization. Furthermore, she celebrated imperfection as artistic truth. She never sought approval; she demanded response. Her work echoed graffiti, noise, and riot energy. Moreover, she saw culture as ongoing rebellion against apathy. She fused literature and life through disobedience. Ultimately, she proved art must disturb comfort. Her underground legacy continues inspiring creators who refuse compromise, showing that cultural resistance remains the heartbeat of freedom and that the truest literature grows from refusal to obey systems demanding silence.

Conclusion

Kathy Acker American writer embodied literature’s purest rebellion. Her life merged philosophy, sexuality, and politics into living performance. Moreover, she destroyed conventions fearlessly. Her writings continue challenging obedience. She believed truth hides within chaos and pain. Additionally, she proved art’s duty lies in confrontation. Her words remain alive, fierce, and relevant. Furthermore, she taught that destruction leads to liberation. Through pain, she found voice. Through defiance, she found meaning. Her artistic spirit transcends death. Ultimately, Kathy Acker American writer transformed literature into revolution, proving that rebellion sustains beauty longer than obedience ever could. Her art endures as manifesto for those who refuse silence, compromise, and conformity, reminding every generation that freedom, truth, and creation demand courage more than perfection or approval.

Samuel Butler, Restoration Period Writer: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/07/03/samuel-butler-restoration-period-writer/

Thomas Pynchon Postmodern Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/thomas-pynchon-postmodern-writer/

The Thirsty Crow: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/10/the-thirsty-crow/

Subject-verb Agreement-Grammar Puzzle Solved-45:

https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/subject-verb-agreement-complete-rule/

To read the poetry of William Dunbar, follow the link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dunbar

Discover more from Welcome to My Site of American Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.